Digital transformation and IT investment

Business investment has all but disappeared in the last five years. Therefore, it is understandable that the appeal for more investment in the drive to digital transformation will unlock innovation and a new route to productivity — namely, greater organisational efficiency and better use of existing resources and assets. However, it is not that simple, as a review of the data illustrates.

In order to pivot the economy to a new business cycle, a renewed stage of capital IT investment is seen as a prerequisite. The general output of such investment could lead to better customer experiences and organisational effectiveness, as these two items are typically claimed as the objectives of such a strategy. This putative result is unqualified — it is an assumption based on data and experiences which date back 20 years, and is not related to the current state of technological investment and stock.

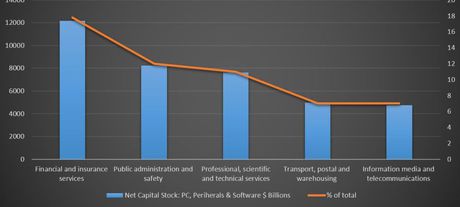

In Chart 1, the capital stock — that is, the amount of money invested in technology in Australian industry sectors — is shown for the five leading sectors. The Finance and Public Administration sectors lead as the most technology intensified and invested verticals with over 30% of total net capital stock. The orange line on the other axis represents the total percentage of each sector as a share of the total. In sum these five sectors account for 55% of all technology investment. The other 14 sectors measured by the Bureau of Statistics constitute the remaining 45% of technology investment between them.

Whether this pattern or disposition of investment and stock is optimal, too intensive or effective is not possible to infer. Within the commercial sectors the level of investment may be aligned to returns on capital expenditure or reducing operational costs, and therefore obvious financial metrics are associated with the degree of investment.

To understand the status of the stock position the data should be examined in relation to the value of each sector. This will allow inferences to be made as to relationships between overall technology depth and capability and the magnitude of a sector’s value. It may also, at least in part, allow for judgement as to the quality and effectiveness of the enabling technology.

Chart 2 shows the change in sectoral value relative to the whole economy. This evolution of value nearly matches the technology investment boom (discussed in the IBRS report, The IT Investment Growth Rate 1981–2020).

The relative performance of different sectors is shown in terms of their share to overall industry real value added in 2015 compared to 1990. The Information Media and Telecommunications sector exhibits the highest change. In 1990 this sector’s share of real value was 2.2%; in 2015 it was 3.5%, which is a 62% increase. Financial and Insurance Services have grown by over 40% in the period. Except for Public Administration, all of these sectors increased their relative value. Transport, Postal and Warehousing grew by just 1% over the period. Public Administration declined 22% and the other sectors that fell were: Education and Training (32%); Accommodation and Food Services (22%); Manufacturing (46%); and Agriculture (15%).

Importantly, the changes in relative value are not directly correlated to net capital stock and hence technology investment. The changes reflect the shifts in the economy and consequently, Manufacturing has declined and Finance has grown.

The relative decline over 25 years in Public Administration as a share of the economy is not especially significant and may be understood as an improvement in the sectoral profile of the economy.

Where this chart and the first chart are useful is in understanding the relationship between technology investment and the aggregate value of the sector. For instance, the net capital stock for Mining is modest, under $2 billion, yet its sectorial share is 32% higher than it was in 1990. This result is skewed because of the huge mining boom which saw the value of its output soar to unprecedented levels. In a similar manner, the Information, Media and Telecommunications’ result is indicative, along with the Finance sector, of a more developed services economy. Their results have been generated by wider institutional and policy changes together with social and demographic dynamics over 25 years. Technology is necessary to the evolution of the changes and the attainment. It is not certain that it is the sole critical variable.

In summary, the data and its interpretation can be understood in the following terms:

- Technology investment, or deepening, is not a guarantee of improved output/value.

- Macroeconomic trends and exogenous forces are highly significant, eg, the recent record of mining, manufacturing.

- The most rapid period of change was within the first decade of the period, ie, when technology investment was at its highest rate coupled with wider reforms and transitions. This follows a standard pattern when initial high-quality innovation produces a leap but further enhancements produce only marginal improvements at higher costs.

The current moves to digital transformation are intended to replicate, as nearly as possible, the efficiency and productivity leap described in the period 1990–2015. Within the context of the data and analysis provided here, it is uncertain if that is a possibility.

While the data used here is aggregate, there will be private organisations and government agencies on various points of the maturity spectrum which may see their requirements differently. In addition, refreshing technology solutions to suit a changed business environment will and should continue, but whether a greater commitment to more technology is the main solution should be debated vigorously and sceptically.

Planning the future with rear-vision perspectives is sure to disappoint, if not fail. Organisations would be better to examine their own situation and discard received wisdom, especially from vendors.

Four ways AI can finally make threat intelligence useful and not just noisy

Done poorly, threat intelligence is noise. But done well, it becomes one of the most powerful...

Australia’s top tech priorities for 2026

It is anticipated that AI will evolve from a pilot project to a productive standard, underpinned...

Why AI's longevity lies in utility, not novelty

The real potential of AI is in underpinning the invisible systems powering everyday business.